An interesting project that doesn’t come along very often. It combined solid limber construction, veneering and also turning. The cabinet itself stores antique zinc records 27 inches in diameter from the 1900’s. A “record player” sits above the cabinet.

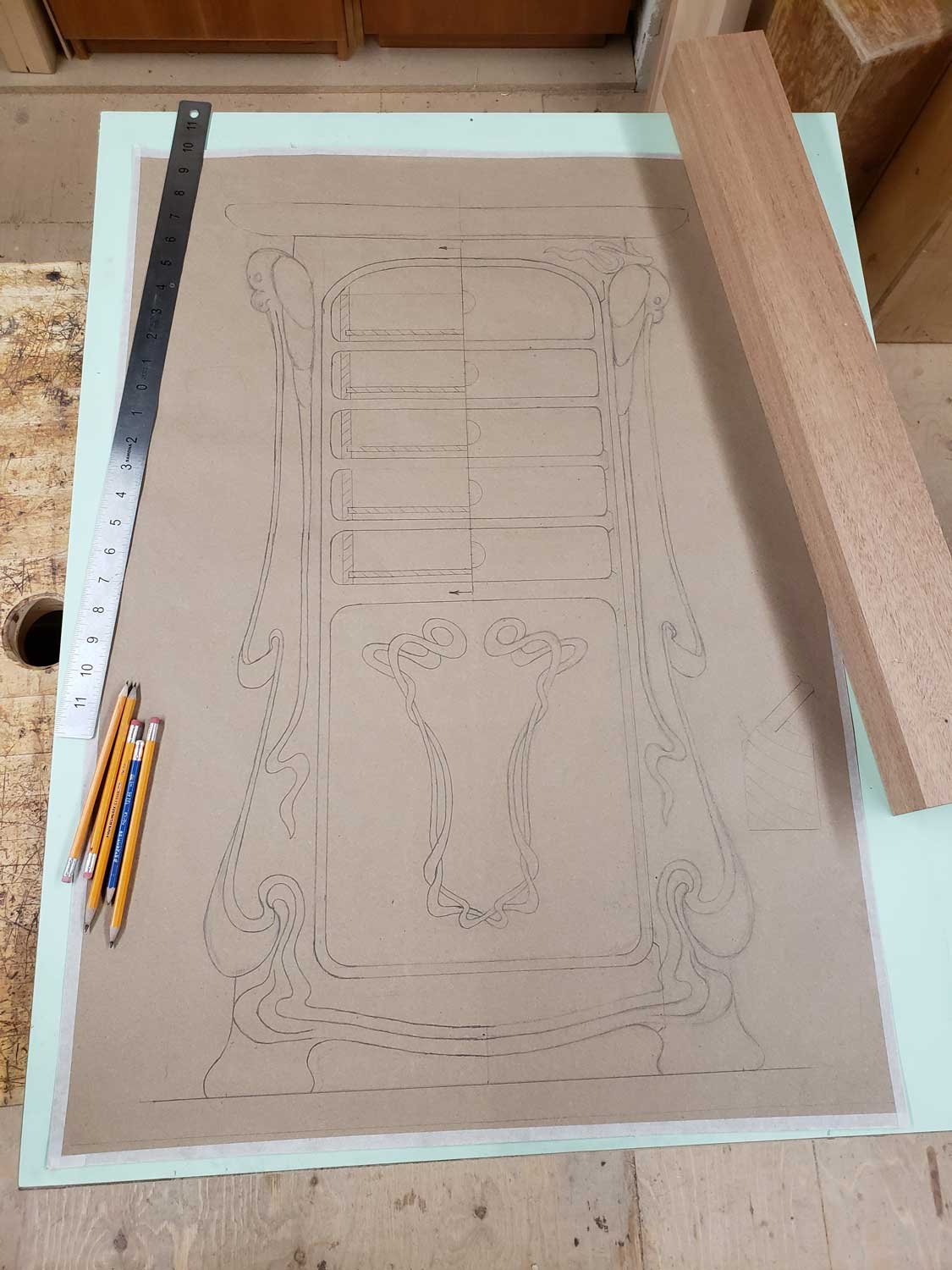

Everything starts with an accurate drawing. I had photographs of the cabinet I was reproducing and basic dimensions.

The rough walnut when it first arrived at the shop. I needed nice grain for this job.

A few of the samples I created trying to match the mouldings on the cabinet. The cutters used on some of these old cabinets are no longer available. I didn’t want to grind cutters for one cabinet so I used portions of the cutters I had available and laminated to create the shapes.

The initial glue ups. Some of the panels were to be veneered afterwards.

Using a portion of a cope and stick cutter to get part of the shape I was matching.

Stacking the moulding to build up the base pieces. A nice clean seam.

Cutting and fitting the mitres on the base.

Checking the base against the drawing.

Fitting the center panel in the base.

The glue-up had to be done upside down because of the shape of the edge. I needed the flat towards the bottom to apply clamping pressure.

Time for veneering. I laid out the panels to decide where the seams should be and how the panels would relate to one another across the carcass.

The four panels ready for vacuum pressing. One panel for each gable and two for the door.

After the panels were pressed they were fielded on the shaper.

The gables all glued up. The edges and backs of the panels were pre-stained so they wouldn’t show bare wood as the panels moved due to moisture.

Cutting and fitting the front door parts. The door was thicker than the gables so I couldn’t use the same cutters as on the gables. I had to enlarge the groove and move it farther towards the back surface than my cutters would allow.

Everything fit well for the dry run.

But for whatever reason the pieces needed a little persuasion from a couple of clamps to stay flat during the real glue-up. Such is life.

All the panels cleaned up and cut to size ready to form the carcass.

Time for the turnings. I had only one piece of 8/4 in the shop that would do. Careful cutting to get nice clean blanks.

Happy with my prototype I hung it above my lathe and began cutting the real posts.

The details were fairly crowded and went from small to large dimeters quickly. The worst was the square shoulder at the top with a groove and then a bead only 1/8” away.

Wouldn’t you know it the post had ten flutes and my lathe has an indexing jig with 48 holes. I had to make an MDF disc drilled with ten holes and mount it externally on a faceplate.

I used a router to cut the flutes because the post was of uniform diameter.

The four posts cut and routed.

Laying out the cabinet pieces.

I cut a piece of MDF to use as a reference for cutting biscuits in the bottom to attach the gables.

Everything worked out nice and clean. I added screws from the bottom later.

Gluing up in sub-assemblies. First the gables to the back.

Now the sub-assembly to the bottom.

Next I cut and fitted the inner panel. This was at an angle inside the carcass. A post was attached later in the center to hang the metal records on.

I made up a web frame for the top.

I had an image of the carving my customer wanted to match. I after scaling I used dividers and a cardboard template to layout the pattern.

There was another layer of moulding before the actual top so I glued it all up to have a look.

Laying out one detail at a time in sequence so they all look the same. I was concerned about the corner detail because I didn’t have a clear picture of what was done on the original. Carving moulding is tough repetitive work. The people who did it for a living had to be so fast to make any money.

Once the carving was done I was ready for the final assembly. The posts were turned with a tenon at the bottom so I glued them into the base first using spacer blocks at the top to align the square sections.

Next the top section was added. The posts were screwed and glued to the underside.

With the clamps removed the cabinet is almost done.

The top panel is secured in place.

The front door was morticed for the lock and the hinges were also cut in. Next the hinges were cut into a mounting strip running along the bottom front edge of the cabinet.

Lastly, a thin moulding strip was added to the top of the door. An escusteon plate will be added later. Once the cabinet was completed it was off to the finisher where it will be colored and given a hand applied finish. A nice period piece that doesn’t come around too often.